AustLit

-

“Don’t call me clever,” she said, “it makes me think I should wear elastic-side boots. Say I am fresh or original. Those are the things that count in writing.” And the merry little face scintillated with mischief. “I have known such clever people fail.”

Sumner Locke, in interview with the Auckland Star (1917)

-

Sumner Locke, if recognised at all by modern readers, is known by her maternity: the birth, when she was thirty-six, of her son and namesake, Sumner Locke Elliott, caused complications that led to her death. That death echoed through her son’s writing, so that more people are conscious of the dim shade of a real women hovering behind Sinden Marriott in Careful, He Might Hear You or Sidney Lord in Waiting for Childhood than are familiar with her life. Few know her as an author, and fewer still are likely to have read her. The decision (by whomever it was made) to name the son after the mother only complicates this process of erasure: the two generations of authors become entangled, and the mother is ultimately overshadowed by the greater fame of the son and subsumed into the autobiographicality of his writing.

-

Yet in the early years of the twentieth century, Sumner Locke was a prolific and well-loved writer in her own right. In London, she was a friend to Katharine Susannah Prichard and Nettie Palmer: Prichard wrote of both Locke and Palmer in her article ‘Two of a Kind – Yet Different’. When Locke died, newspapers in Australia and New Zealand wrote obituaries for the ‘well-known Australian novelist’ (Sydney Morning Herald, 19 October 1917, p.8). Mary Gilmore dedicated verses in The Australian Worker to her (right).Endnote 1

Newspapers at the time even reported various people as having said, of her death in childbirth, ‘Let us hope the son will prove worth the sacrifice’ (‘Said That’, p.4).Endnote 2 The public response to her death does not speak to an unknown author.

So who was Sumner Locke?

-

Born Helena Sumner Locke in Sandgate, Brisbane, in 1881 to the Reverend William Locke and his wife Annie Seddon, she was raised in Melbourne from 1888. William Locke’s father, also William, had worked for twenty years with the 7th Earl of Shaftsbury in the establishment of the Ragged Schools in London (‘Hostel for Working Girls’, p.10); the younger William obtained a BA from Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, before arriving in Australia (‘Crossed the Bar’). Annie Seddon was the daughter of a clergyman, Reverend David Seddon, inaugural incumbent of Christ Church in St Kilda (‘Personal’, p.1): he and his daughter arrived in Australia in 1852 (‘Crossed the Bar’), and Annie married William in 1868, in Brighton, Victoria.

William and Annie had a large family: eight children (seven daughters and one son) survived both parents, and three other daughters died in infancy.Endnote 3 Their children included daughter Lilian (later Lilian Locke-Burns), who was a significant member of the early women’s rights movement in Australia (as an active and vocal member of such organisations as the South Melbourne Women’s Progressive League and the United Council for Women’s Suffrage) and later of the Labor movement.Endnote 4

-

Sumner Locke made her own living from a relatively early age, and well before her father’s death in 1908. A New Zealand newspaper, the Evening Post, reported in 1908 that her first work was clerical:

She always had a leaning towards stage work, but as the daughter of an Anglican clergyman she was severely discouraged in her theatrical aspirations, and in due course, Miss ‘Summie’ had to go forth and clerk in a commercial office. (‘Women in Print’, 1 October 1908, p.9)

Her clerical work cannot have lasted long, however. As early as 1899, she was becoming known as an elocutionist. She had previously enjoyed some success in amateur elocution competitions (‘Exhibition’, p.4). In June 1899, a report in Melbourne theatrical newspaper Table Talk noted:

Miss Sumner Locke, who is making her way as a reciter, is the daughter of a clergyman, whose failing health prompted her to strike out for herself by cultivating her dramatic talent. Miss Locke is not yet twenty, and a few months ago won a gold medal for elocution in the A.N.A. examinations (2 June 1899, p.8).

By the following year, she is described in Tasmanian newspapers as ‘Miss Sumner Locke, the charming and talented elocutionist, from Melbourne (who was honoured with a double recall at a recent concert in our Town-hall)’ (Mercury, 10 March 1900, p.3). Endnote 5

-

Locke also lent her talents to fundraising, appearing in several performances in aid of the Bacchus Marsh Agricultural Society in the early 1900s: her father was an Anglican minister at Bacchus Marsh for some years and this work, like her work for the Progressive Women’s League, showed Locke’s strong inclination to lend her time and talents to the causes of her family.

She continued her involvement with theatre throughout the early years of the twentieth century, continually pushing herself into new aspects of the performing arts: 1903, for example, saw her as both stage manager and lead actor of three-act farce The Tivoli Girl at the Melbourne Comedy Club (Table Talk, 16 April 1903, p.22). Whether by choice or not, Locke’s acting work never extended to professional theatres: she remained firmly based in amateur and repertory productions, often for charitable benefit.

Unsurprisingly, Locke began writing her own plays: the earliest play traced to date is a one-act farce called My Excellent Cousin (1902), which was acted under Locke’s direction at a conversazione at the Old Trades Hall in Carlton. The show was performed for the benefit of the Women’s Progressive League, with which Locke’s sister Lilian was closely involved: Locke and a third sister, Blanche, took two of the roles, and Miss Nest Malcolm (a keen amateur actor) the third (‘[Untitled]’, 1903).

-

The best known of Locke’s early plays is The Vicissitudes of Vivienne. Performed by a cast of amateur actors, the play was staged at Her Majesty’s Theatre in Melbourne in 1908, by permission of the manager, J. C. Williamson. A four-act drama, it included, according to an untitled piece in the Gadfly, ‘comedy of a refined class in parts’:

Amongst the characters are a philosopher, grey and idealistic in the extreme, a woman who is his twin soul, a man who looks on, and a masculine woman who it is expected will bring down the house, a few men who invariably differ in their peculiarities, a crowd of society walkers-on, and some characteristic men servants. The heroine, Vivienne, passes through many exciting episodes “to right the wrong” worked by others, comes on in one part dressed as a boy; in another masquerades as a scrubbing-woman in the philosopher’s house. (p.7)

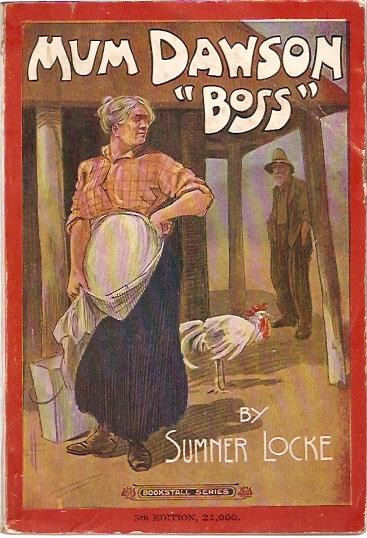

Locke’s first works of prose had appeared the year before: short stories and poems in The Australasian and The Native Companion. She followed Vivienne with other plays, including the short tragedy A Martyr to Principle (co-written with Stanley McKay, of amateur theatrical group The Sydney Muffs), in which a bridegroom stricken by tuberculosis drinks poison on his wedding morning, to spare his bride the difficulties of his care: it was produced as a curtain-raiser to a 1909 charity production of Niobe by Edward and Harry Paulton (‘The Sydney Muffs’). When Leopold Stach and Nellie Strong joined forces at the end of a successful New Zealand tour and left for the American vaudeville stage, they took with them their own material: ‘a number of sketches specially written for them — two from Christchurch writers and the remainder from the pen of Miss Sumner Locke, of Sydney’ (‘Mimes and Mummers’, p.2). She later became widely reported to be the first Australian woman dramatist to have a play produced by a commercial theatre company in Sydney, when the Bert Bailey Company staged her adaptation of her own novel, Mum Dawson, 'Boss', in 1917.

-

In 1912, with dozens of short stories and a variety of theatre experiences behind her, Locke left Australia for London on the Runic. In an interview with a New Zealand newspaper when she was en route to the United States in 1917, she recalled:

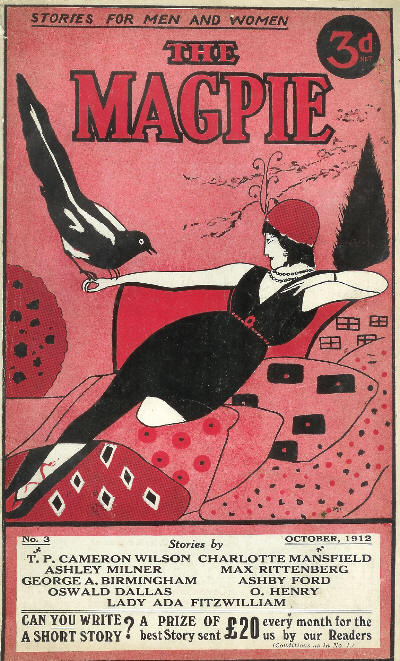

When I went to London last time […] I carried a suit case and a small typewriter. I had my ticket and £70. Yet I made good. Soon after I arrived, one of the good magazines offered a prize of £20. I won that prize from all London, and the money tidied me over any stress. The first thing I did was to write stories when I landed in London, and one of them carried off the money. (‘A Woman Dramatist’)

The prize in question was for a short story published in a literary magazine called The Magpie, and — so later rumour had it — ‘was awarded under the impression that she was a man’ (‘An Idle Woman’s Diary’, p.7). Locke’s output during her three years in England has not yet been traced, although she made her living as a writer of fiction and as a journalist during that period: Deborah Jordan notes of Locke that ‘she caused a sensation when bill-boards a foot high advertised her poems’ and, according to Katharine Susannah Prichard, once ‘achieved an interview with an ‘Uninterviewable’ editor, by making love to an office-boy’ (p.74). As early as 1913, Australian newspapers reported that Locke ‘has caught the eye of the gorgeous magazine editors, and she is supplying her sparkling phatter to them at the rate of a sovereign per running foot’ (‘Personal’, 1913).

-

Locke returned to Australia in 1915 on the ill health of her mother: in her years overseas, she had kept a space for herself in Australian literary spheres by publishing regularly in Australian journals. In the two years between her return and her death, her works appeared in newspapers and periodicals from Melbourne to Perth. She had begun to write novels before her departure for England, beginning with Mum Dawson, 'Boss' (1911), a humorous novel of selection life. She followed this with two works in a similar vein — The Dawsons' Uncle George (1912) and Skeeter Farm Takes a Spell (1915) — before publishing what was to be her final novel, Samaritan Mary (1916), a novel set in the United States. She clearly intended further novels: among the papers donated by her son to the State Library of New South Wales is at least one unpublished novel, The Blue Sky Gentleman Endnote 6.

She also had her greatest dramatic success in 1917: Bert Bailey’s company staged her play, Mum Dawson, 'Boss', at the end of their Sydney season. Newspapers claimed that ‘Miss Locke has the distinction of being the first Australian woman dramatist to have a play produced in Australia’ (‘Personal’, 1917), and advertisements spruiked the play as ‘screamingly funny’ and ‘something altogether new in Australian plots’. Locke herself said of the experience:

To produce a play properly with a man who knows the business as Bert Bailey does, one wants to be very cheerful, or very dead. Speaking personally, I should say it is the greatest experience of a mental landslip that one can have without losing balance altogether. (‘Author v. Producer’).

Critics recognised that the play drew inspiration from its predecessors — ‘J. Rufus Wallingford comes to Our Selection’, the reviewer for the Sun succinctly phrased it (‘Mum Dawson, Boss’). But they recognised the skill behind the work, which they said ‘justifies the management’s policy in looking for its material of comedy in the work of Australian writers’ (ibid).

-

In 1917, then, Locke seemed on the cusp of real fame. But although she did not know it when she wrote her war-time romances, the end of Sumner Locke’s life was her own war-time romance. On 20 January 1917, the day Mum Dawson, 'Boss' premiered, she married Paymaster-Sergeant Henry Logan Elliott, a childhood friend. On 6 February 1917, he sailed for England with his regiment, leaving behind a now-pregnant wife he would never see again.

Some months later, Locke undertook a combined book tour / research trip to America, accompanied by Shirley Huxley, an actor who had appeared in the Australian film The Shepherd of the Southern Cross (1914) and who remained in the US to make her only American film, A House Divided (1919) (‘Social Gossip’). From Vancouver, Locke travelled by boat to Seattle and train to San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Phoenix. From Phoenix, she travelled to and settled in Ray, Arizona. In the 1950s, inhabitants were moved out of Ray before the original township was swallowed up by the open-cut copper mine, but in 1917, it was a thriving mining town.

-

Locke described it as “a place one-eyed and high-browed, with mixed humanity”, and stayed in the home of one of the mine managers:

Our house clung to a shelf of rock high to the side of the canyon, and the crags looked as if they were scraping the sunset coloring off the sky. There was some desert, ash soil below, rock, cactus, and more ash soil and cactus, and Mexicans and dust and a little more dust, and other kinds of dust and just dust. (‘Some Republic’).

From Arizona, she went to Texas, from Texas to New Orleans, and from New Orleans to New York. In New York, “I did real business. Went over the red carpet of publishers and one almighty play company. After days of this kind of thing and smaller affairs — studio dinners with Sass, Essen, Harry Julius, and Douglas — I hiked out for Boston” (‘Some Republic’) Endnote 7. She settled in Boston for two months, working solidly on her writing.

She tried to cross the Atlantic to England to be closer to her husband, who was then on active duty in France. But the ocean was closed to civilian traffic and she returned to Australia at the end of July 1917. She died, on 18 October 1917, of eclampsia, the day after giving birth to her son.

You might be interested in...