AustLit

-

There is no world, there are only islands.

– Jacques Derrida

People try with an increasing despair to live, and to come to something, some place, or person. They want an island in which the world will be at last a place circumscribed by visible horizons.

– Robert Creeley

-

This subset is one of the Research Projects of the AustLit resource, and is under the direction of Professor Philip Mead, at the University of Western Australia. It aims to provide bibliographical information about Van Diemen’s Land and Tasmanian writing, and includes biographical information about authors who were born in, visited or whose writing has been substantively influenced by Van Diemen’s Land or Tasmania, as well as about publishers, literary societies, relevant book history, archival holdings, and places of significance to Tasmanian writing. The AustLit resource allows you to search within these categories of ‘Tasmanian regional literature and writers.’ The subset builds on previous bibliographical work in Australian literature that, from early in the twentieth century, recognised the distinctive literary culture of colonial and modern Tasmania (see ‘Relevant bibliographical work, library and archival resources’). This introduction is designed to be used in conjunction with the database as a finding tool for ideas about the literature of Tasmania. It offers some critical outlines of authors’ careers and individual works, some thematic focuses for critical reading and research in the literature of Tasmania, some theoretical reflections on the island and literary regionalism, and some contextual references to the world literature of islands.

This critical introduction is structured around the periods of Tasmanian cultural history: the deep time of Indigenous or Palawa Tasmania (Trowenna) and its survival into the present; the first decades of British settlement from 1803 to 1854 (the end of transportation); the second period of colonial history from 1855 to Federation, beginning with the change of the colony’s name from Van Diemen’s Land to Tasmania; the twentieth century, and the present. It also provides a thematic guide to the Tasmania of the mind, or Tasmanian writing as a distinctive literary imaginary, and as an identifiable regional subset of both Australian literature and the world literature of islands.

In Italo Calvino’s novel The Castle of Crossed Destinies (1973) there is a moment where the narrator realises that stories don’t proceed along thin, linear planes, or straight singular lines. The act of reading produces a dense forest of story in whichever direction the reader proceeds, it’s unending. This sounds like reading the literature of Tasmania: the topography is awesome and astonishingly varied, enhanced by its insular and relatively remote nature. But in the atlas of the imagination, as this introduction aims to suggest, the island is even more densely layered – Trowenna, Taprobane, Van Diemen’s Land, Tsalal, Transylvania, Tasmania. In fictions as well as real, historical experiences of the global south, Tasmania has had an exotic and multi-faceted presence for centuries, which has built up a thick narrative discourse about the island. Writers have even been prompted by this narrative density into creational linguistics, as if the place deserved an endemic language of its own – the dialect of the lost tribe in Louis Nowra’s play: The Golden Age, the regained speech of his narrator Hannah in Into That Forest, the idiolect of Peevay, one of the narrators in Matthew Kneale’s English Passengers, Richard Flanagan’s Vandemonian patois ‘dementung’ in Gould's Book of Fish, a ‘bastardised dialect that was part blackfella, part whitefelon.’ Underlying these literary inventions are remnants of the Palawa (or Parlevar) language from explorers’ and missionaries’ word lists, French place-names, contemporary Indigenous language retrieval projects, and the varieties of transported English. The genres of island writing, always relevant to the corpus of Tasmanian literature, are both foundational to the Western literary tradition and complexly instantiated through history and hemispheres. This guide, then, recognises the historical phases of ancient habitation, first contact and settlement, with its contradictory modernities, down to the present but doesn’t try to constrict the literature of Tasmania to a linear history. It doesn’t pretend to be comprehensive about a literary discourse that extends in every direction, that can be read backwards as well as forwards. It aims rather to provide a set of thematic and historical waypoints for navigating around the richly varied literary biota of this island state.

-

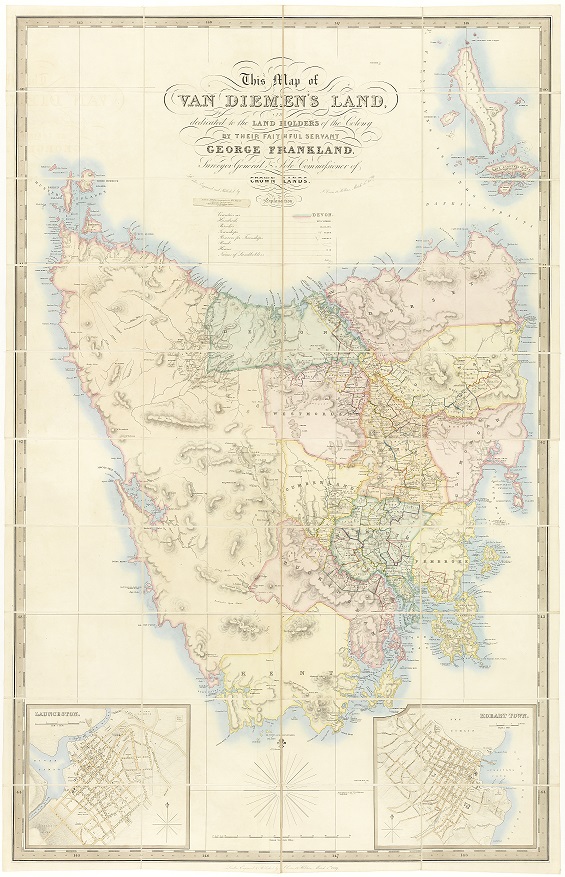

When the Dutch maritime explorer Abel Janszoon Tasman discovered a coastline in the Southern Ocean between 40˚ and 44˚ South in 1642 and named it Van Diemen’s Land, after the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies in Batavia, he probably assumed it was part of a larger landmass rather than an island. This mentality of exploration is a sign of southern hemisphere difference. The predominance of assumptions of insular geographies in the northern Age of Discovery is obvious for centuries, while in the southern hemisphere it is the myth of the Great South Land, one gigantic mainland, that dominates early cartographical thinking. In this sense Tasman’s outline initiates Tasmania’s history as a kind of antipodal or anti-California: its insularity would take a long time to prove, just as the legend of the Island of California would persist for centuries. For, it was more than 150 years before the geographical fact of Tasmania’s islandness was known in the West. Up until the explorations of Bass and Flinders in 1798, Van Diemen’s Land existed as a fragmentary cartographical outline, a floating string of coastline with an unknown relation to the possibly continental vastness of New Holland or to some other terra Australis incognita. Either way it was assumed it was a ‘land’ rather than an is-land and it often appeared on presumptive maps of the southern hemisphere up until the end of the eighteenth century, as in Jacques Nicolas Bellin’s ‘Terres Australes’ of 1753, as a south-eastern, sub-continental extension of Nouvelle Hollande. Despite these cartographers’ ignorance of plate tectonics, such maps unwittingly reproduced the modern geologists’ Pleistocene-era Sahul. The revelation of Van Diemen’s Land’s ‘proven insularity,’ when it did become known, was news: for example a letter conveying this fact was published in the Gentlemen’s Magazine for July 1800 (Aurousseau 485). Christobel Mattingley, inspired by Jacob Gerritsz Cuyp’s c.1637 portrait of ‘Abel Tasman, his wife and daughter’ in the National Gallery of Australia, has written a young adult historical novel, My Father's Islands: Abel Tasman's Heroic Voyages (National Library of Australia, 2012) about Tasman’s voyages from the perspective of his daughter Claesgen.

In geological time, Van Diemen’s Land had indeed been physically part of the mainland continent of Australia, 8,000-10,000 years before the end of the last glaciation flooded the plains and valleys that now lie beneath Bass Strait. Although Tasmania, as a plate-margin rather than a hot-spot island, has been heading away from the southern super-continent of Gondwana, along with Antarctica and New Zealand, for millions of years. So Tasmania’s epochal history of insularisation is both geochronological and cartographic. Much later it would also be geopolitical and imaginary, an island state within a settler federation; a distinctive presence within a national literature and within the transnational and transhistorical discourse of islands and islandology. During the bicentennial of white settlement in 2003-04 the state’s Premier at the time, Jim Bacon, added another layer to Tasmania’s awareness of its own insularity by referring to the place as an archipelago of one large island surrounded by more than 340 smaller islands, urging Tasmanians to think of their state not so much as an island, but as an island region (see Cranston, ‘Islands’; Mead and Stagg 317). Geoscience Australia defines the Tasmanian archipelago as made up of a curiously precise 1,000 islands, so again, the definition of insularity is variable. The archipelagic experience of living in Tasmania is certainly coded into popular expressions like ‘the big island’ or ‘the mainland,’ which can refer to either Tasmania or continental Australia depending on local context. These expressions also reflect the fact that the state includes, politically and administratively, the Bass Strait Islands to the north and sub-Antarctic Macquarie Island, at the edge of the convergence, to the south, just as in colonial times Van Diemen’s Land included, administratively, Norfolk Island. This archipelagic awareness nested within ‘big island’ consciousness includes Maria Island, Bruny Island, Sarah Island, The Isle of the Dead, Three Hummock Island, Schouten Island, Erith Island (see Joanna Murray-Smith, Judgement Rock, 2002), even Maatsuyker Island (see Robyn Mundy, Wild Light, 2016) – all places of historical, tourist, artist-community and family history associations, and with many literary aspects. Islandness then, as far as Tasmania suggests, is in reality a plural and multi-layered condition – in deep time, in history, and in the imagination.

-

Van Diemen’s Land, the first European name for Tasmania, perhaps because of its unknown extent and its antipodean distance from Europe and North America, was also a name for the uttermost edge of the world, the southern hemisphere equivalent of Ultima Thule. That’s probably what it signified in Emily Dickinson’s poem ‘If you were coming in the Fall,’ with its lines about counting fingers in a child’s game, ‘Subtracting till my fingers dropped/ Into Van Diemens land’ (Pierce 217). The end of the world had been a convenient place for Jonathan Swift to locate his other-world islands, Lilliput and Blefuscu (‘discovered, A.D. 1699’) in Gulliver’s Travels (1726). The imaginary cartography of the frontispiece to the first edition of the novel adapted the chart of Van Diemen’s Land from Tasman’s 1642 voyage, showing the incomplete coastline to the south-east of Gulliver’s ‘remote nations.’ Van Diemen’s Land’s fragmentary coastline is one of the markers, ironic and otherwise, of Gulliver’s fictional narrative of maritime exploration. Thus Tasmania, as a kind of cartographic zygote, has an embryonic presence at one of the inception points of the English novel. Some readers of Tasmanian material culture view the pre-settler association of Van Diemen’s Land and Gulliver as prefiguring a ‘collocation’ of Tasmania, island, colony and miniaturisation in terms of the exilic island imaginary (see McMahon, ‘Tasmanian Lilliputianism’). Van Diemen’s Land is also the last outpost of human settlement for Edgar Allen Poe’s hero in The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1837) on his expedition to the Antarctic. Paul Giles reads Poe’s version of Van Diemen’s Land, Tsalal, or a disfigured Tasmania, as a sign of Poe’s anxieties, as an American northerner, about race and the violent primitivism of ‘black’ peoples of the South (Antipodean America 139). Another North American literary and voyager connection is Amasa Delano’s (1763-1823) account of his visit to Van Diemen’s Land in his Narrative of Voyages and Travels in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres (1817). In his account of sailing around the East coast of Tasmania and in Bass Strait, Delano describes rescuing Lt. John Bowen from Cape Barren Island. Bowen’s ship Integrity had lost its rudder on a return voyage from Sydney. Delano relates another episode in Bass Strait when he nearly drowned taking a barrel of fish ashore from one of his ships: 'About midway between the Pilgrim and the shore, while crossing a horse market, (a sailor’s phrase for a rough irregular sea, the waves rising all in a heap, occasioned by two tides meeting,) the water rushed so rapidly into the boat, that in less than two minutes she sunk like a stone to the bottom, leaving us floating on the surface,' (n.p.). An extract from Delano’s 1817 narrative, A Narrative of a Voyage to New Holland and Van Diemen's Land was published in facsimile by the Cat & Fiddle Press in Hobart in 1973 (see Delano). Delano’s journals were the source for Herman Melville’s 1855 novella ‘Benito Cereno,’ including his narrator in that story.

-

By the time of first British settlement in 1803-4, Van Diemen’s Land had been annexed to New South Wales but its old Dutch name proved resilient. In fact the island has been Van Diemen’s Land much longer than it has been Tasmania. The British colonising extension of New South Wales, following settlement at Sydney Cove in 1788, was a response to the French maritime interest in the landmass, to French territorial claims to western New Holland and the possibility of France ‘gaining a footing on the east side of these islands’ (King 249). French explorers Bruni d’Entrecasteaux (1792) and Nicolas Baudin (1802), driven by the spirit of the Enlightenment, were keen to match Cook’s successful English expeditions in the Pacific, but the French voyages that included Van Diemen’s Land exploration were disabled by the political divisions of revolutionary France they carried with them. These idealistic but troubled voyages surveyed and studied the Indian Ocean side of New Holland and its southern extension, ‘Terre Napoleon.’ But it was the perception of French territorial claims of Citizen Baudin’s mission to explore the east coast of Van Diemen’s Land, and the anxiety about ‘an Australian Pondicherry’ on the shores of Storm Bay, that galvanised the British into action (West 28; see also Carter and Hunt). English Van Diemen’s Land, then, is founded as a border-securing extension of penal New South Wales and begins its history as a notorious prison island. The French coastal interlude in Tasmanian history, though, with its encyclopaedist, botanical and artistic purposes and its sometimes happy encounters with Aboriginal people – as in D’Entrecasteaux’s second visit to Recherche Bay in 1793, in contrast to summary Dutch commercial appraisal and vicious English land-grabbing – turns into a kind of myth of alternative history. Counterfactual French Tasmania, always imaginable from the many French place-names of the southern and eastern coasts of Tasmania, as well as from the artworks of Baudin’s research team, threads its way through later representations of the island’s history and culture. Although, in the history of French encounters with Van Diemen’s Land, Marion du Fresne’s visit in 1772, with its misunderstanding and violence, is more typical of new world encounters.

-

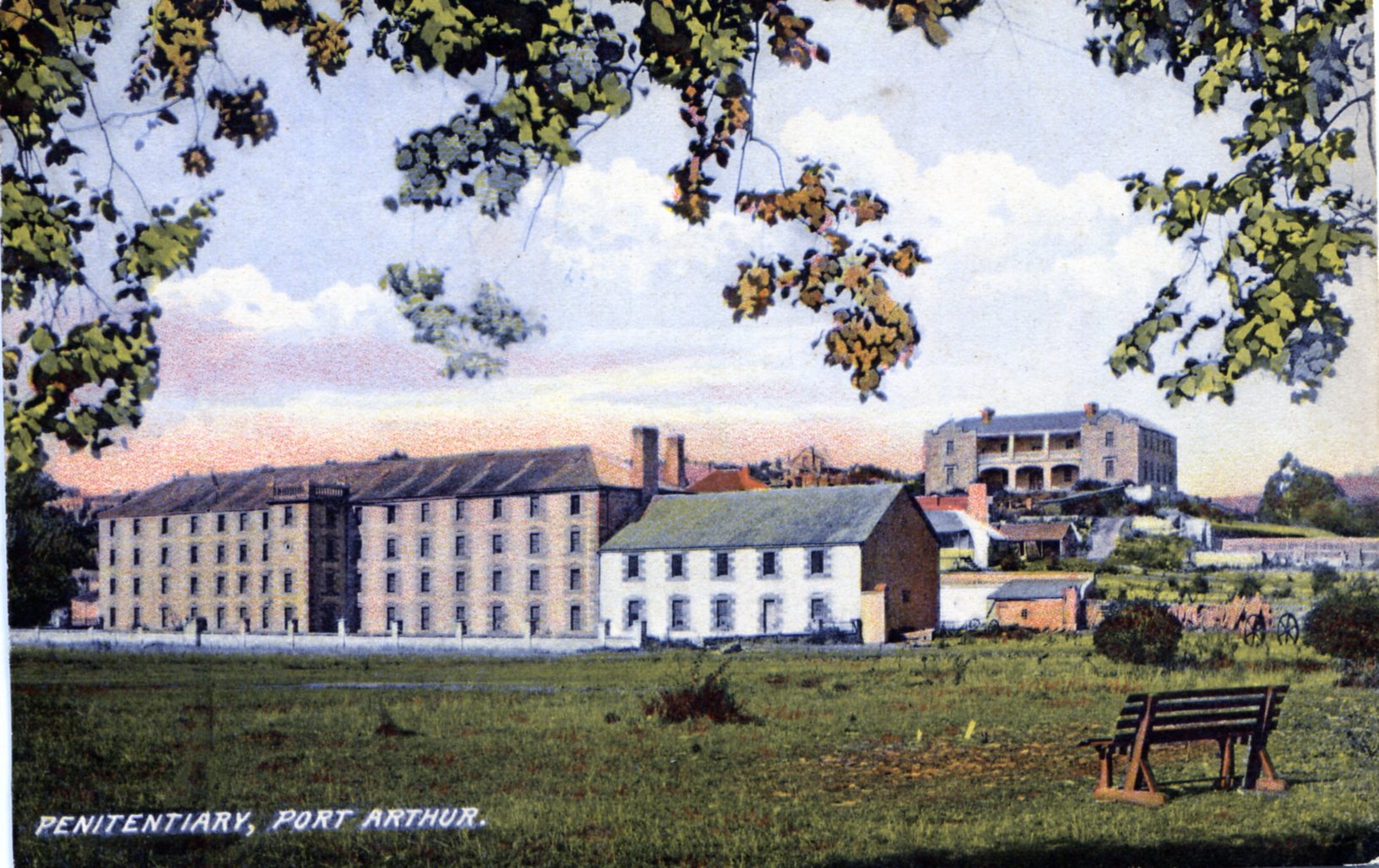

At the beginning of the nineteenth century Van Diemen’s Land became an island penitentiary for transportees from Britain and its colonial dominions, and a site of secondary punishment for convicts from mainland New South Wales. From this point Van Diemen’s Land becomes not just the end of the world but a legendary place of banishment and cruelty. Writing about the colonial period includes folk songs and ballads like ‘The Black Velvet Band,’ ‘The Braemar Poacher’ and ‘Maggie May’ and narratives by convicts and ex-convicts, contemporary writing about convicts and the system that ruled them, and a long and evolving tradition of literary representation of the convict past that stretches down to the present.

In 1825 Van Diemen’s Land achieved a degree of administrative and judicial autonomy from New South Wales. When self-government was established in mid-century, a parliamentary petition was sent to the English Queen requesting a new name for the colony – Tasmania – agreed to by Victoria in 1855. The reason the colonists took this step was that the name Van Diemen’s Land had become indelibly stained with the colony’s history of ‘bondage and guilt’ and with the violence of the genocidal ‘Black Wars’ of the 1820s and early 1830s (see Henry Reynolds’s important article ‘”The Hated Stain”: the Aftermath of Transportation in Tasmania’ in Historical Studies 14.53, October 1969, 19-31). The name Tasmania had, in fact, been in circulation from very early in the colony’s settler history, An Elegant Imperial Sheet Atlas, for example, published in London in 1808, included a map with both the names Van Diemen’s Land and Tasmania (see Giles, Antipodean America 139). ‘Tasmania,’ then, acknowledged Dutch maritime heritage but also facilitated the repression of ‘reminiscences of a painful nature’ (‘Editorial,’ 1856). John West deliberately chose that proleptic name for the colony in his History of Tasmania, first published in 1852, because it was popular, melodious and literary. ‘Tasmania’ meant a fresh start, a new history. The impracticality of Captain James Vetch’s suggestion for ‘geographical nomenclature’ of Australia in a 1938 paper in the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society is obvious: Vetch’s map took the name ‘Tasmania’ off Tasmania, gave it to an area of north-western Australia and devolved Tasmania back to Van Diemen’s Land.

Far from being forgotten, though, Van Diemen’s Land’s convict past was revived imaginatively in the second half of the nineteenth century by writers of popular fictions like Caroline Leakey, in The Broad Arrow (1859) and Marcus Clarke, in His Natural Life (1870-4), both works that remain in print today. And Tasmania’s penal history has continued to fascinate writers up until the present. Contemporary writers such as Andrew Motion, Matthew Kneale, Bryce Courtenay, Richard Flanagan, Rohan Wilson, Christopher Koch (in his last novel, Lost Voices 2012) and Lenny Bartulin (Infamy, 2013) like many before them, continue to revisit the archive of Vandiemonian history, re-imagining the world that produced it from many different angles. This archive of Tasmanian history, like the island’s name, is a conflictual source of remembering and forgetting. This Vandiemonian theme is complex and multilayered, and proliferates across periods and forms, sometimes in extreme ‘Gothic’ inflections, sometimes in less dark, more colourful modes, sometimes functioning as an island imaginary alone, sometimes as a broader national mytheme. As this list of writers suggests, though, it is predominantly gendered as male.

-

Other themes that emerge from writing in the ‘Tasmanian’ era include the utopian or Edenic island, the island of extinction and genocide, Tasmanian Gothic and melodrama, the social and political laboratory, the haunted landscape of submerged or vanishing history, the getaway from society, Little England, the double or ambivalent island: heaven and hell; gothic and pastoral; hydro-industrial utopia and world-heritage wilderness (see Jetson). The emergence of these themes is temporally uneven and generically very varied. An early precursor of Romantic writing about place by mid-twentieth-century Tasmanian authors like Charles Barrett, E.T. Emmett and Michael Sharland, for instance, occurs in John Mitchel’s 1854 account of his time as a political exile at Bothwell in the Tasmanian Midlands, Jail Journal. There he writes: ‘why should not Lake Sorrel also be famous? Where gleams and ripples, purer, glassier water mirroring a brighter sky? Where does the wild duck find securer nest than under a tea-tree fringe, O lake of the south!’ (Mitchel 286). This Romantic scene of the Interlaken district, where he would meet his fellow Irish exiles Kevin Izod O’Doherty and Thomas Meagher, must have been affected by a memory of Ireland because otherwise he thought of Tasmania as a ‘small, misshapen, transported, bastard England’ (Pierce, ‘Highlands’ 90). The convict or Vandiemonian theme, arguably, is generically thicker and more cross-hatched with revisions and critique the further away from the convict past one gets. This historical depth and thematic density of the literature of Tasmania is not only the product of ‘a crop of literary talent quite out of proportion to its limited population’ (Scott 19), but is supported and enhanced from early on by a rich infrastructure of newspapers willing to publish locally written literary work, of book publishing, libraries and collection, literary scholarship, bookshops and literary societies.

-

A subset like this one defines a body of literary work by territorialising it. So it necessarily suggests or marks its difference, its boundaries, its exceptionalism, perhaps even its naturalness. These various effects need to be treated with critical awareness because there is only an imaginary, always mediated relationship between the geographical entity Tasmania and writing that references it. Literary territory is always a rhetorical construction. Nevertheless, space becomes valued place when it is written, place seeps into and grows around words, and spatial and geographical representations are some of the most recognisable and valued of literary effects. Regions may be uncertain, even dubious, entities but they are also beguiling (Pierce, ‘Highlands’). The thematic map to the territory of Tasmania provided by this subset will hopefully allow the kind of testing and continual rereading that this kind of ‘regional’ collectivising of authors and works tends to produce.

At the same time it’s worth recalling that the political and social reality of modern Tasmania has been formed by a population’s relation to place that is unlike anywhere else: the Australian Greens, for example, now a national political party, but begun in Tasmania, has a genealogy going back to the United Tasmania Group in the 1970s and the tragic flooding of Lake Pedder in 1972. The art of wilderness photographers Olegas Truchanas and Peter Dombrovskis and painters such as Max Angus was part of environmental action for the preservation of wilderness and forests. In other words, place has a very particular real-world valency for the Tasmanian polis, it has shaped and continues to shape its political, economic and cultural institutions like no other region of Australia (see Cica). And there is a complex relation between this endemic (sometimes Edenic) reality and the political imaginary, a product of both lived, historical emplacement and the consciousness of place it has produced. The bioregional imagination has been an important contributor to community building and to the definition of polity in Tasmania, and includes ‘place-conscious literature, art, natural-history writing and thoughtful daily living’ (Robin, ‘Seasons and Nomads’ 278). For a compelling illustration of this dynamic see Richard Flanagan’s account of the public meeting of the Greens, in Hobart, at the end of his chapter ‘The Masters of History’ (Pybus and Flanagan 122-35).

Perhaps the most productive perspective on the literature of any region follows from the acknowledgement that regions are also worlds. In this sense no island is an island, no regional literature is entire of itself. As Derrida writes, we ‘do not know what it is, world, what being it is’ but one path to an understanding may be in the question of what a region is (97). To this way of thinking islands are small continents, as Henry David Thoreau sensed: ‘An island always pleases my imagination: even the smallest, as a small continent and integral part of the globe’ (258). Previous cartographies underlying ‘regional’ literatures have sometimes been distorting in their presuppositions or anxieties about metropolitan, usually national centres of cosmopolitanism and cultural density, and separate, pre-modern life-forms or temporal delays in the spread of a singular modernity in outlandish regions (see Shipway). New, less tendentious chorographies now allow us to think of regional literary worlds as mediated by the cosmopolitan, and vice versa, simultaneously local, national and international, as bioregional, sub- and/or trans-national, but with global and hemispherical networks of filiation. As sites of both cosmopolitanism and displacement, of multiple modernities, of isolation and polysituatedness (Kinsella, Polysituatedness). ‘Locality is the only universal’ (John Dewey, qtd in Giles 11). This is especially the case with Tasmania because of the pre- and co-existence of the literature of islands, a virtual sphere of historical, transcultural thematics that envelops and inflects Tasmania’s own distinctive insular discourses. This imaginary aspect of the world includes the generalised romance of islands (Ballantyne’s Coral Island), Lawrence Durrell’s islomania, from Reflections on a Marine Venus (Atlantis, Tahiti), the enigma of islands (Elysium, Rapanui, Sacks’ Pingelap and Pohnpei), the utopian or dystopian social laboratory (Utopia, Paul et Virginie’s Mauritius, Dr Moreau, Huxley), the fantasy island (Yeats’ ‘Innisfree’), island cities (Calvino), the castaway or desert island (Robinson Crusoe, Swiss Family Robinson), the island home (Bergman’s F̊arö, Walcott’s St Lucia), empire islands and problematic shores (The Tempest), the prison, exilic or devil’s island (Alcatraz, St Helena, Îles du Salut, Elba, Charrière, Christmas Island), the monastery island (Lindisfarne, Skellig Michael), the quarantine island or lazaretto (Kamau Taurua, Spinalonga) and multiple imaginary and speculative cartographies, like the isolario of the fifteenth century (see Gillis 42-3; Shell, ‘Preamble’). An element of islandology, linking prison islands, is at work in the legend that all the willows in Tasmania are descended from the tree over Napoleon’s tomb on St Helena, including the one planted by Lady Jane Franklin at Willow Court, New Norfolk.

-

This discourse of insularity is a predominantly northern hemisphere one and there are many powerful Eurocentric and circum-Atlantic archetypes at work within it whose history of transportation, appropriation and adaptation need to be monitored within the southern, Tasmanian setting. Just one example: what kind of adaptations of the décor of Jules Verne’s masculinist model of insularity, as analysed by Roland Barthes in Mythologies, are there in the literature of Tasmania?

Imagination about travel corresponds in Verne to an exploration of closure, and the compatibility between Verne and childhood does not stem from a banal mystique of adventure, but on the contrary from a common delight in the finite, which one also finds in children’s passion for huts and tents: to enclose oneself and to settle, such is the existential dream of childhood and of Verne. The archetype of this dream is this almost perfect novel: l’Ile mystérieuse, in which the man-child re-invents the world, fills it, closes it, shuts himself up in it, and crowns this encyclopaedic effort with the bourgeois posture of appropriation: slippers, pipe and fireside, while outside the storm, that is, the infinite, rages in vain. (65)

A defining aspect of Tasmania’s distinctiveness is the coincidence of its geography with its political status, the only such Australian state. This geopolitical status is double, though, because despite the separateness of the island, ‘another country’ in some tourist literature, the adherence of the Tasmanian population to the Federal ideal is a matter of political record, reaching back no doubt to the sense of being the second colony, not that much younger than Sydney, a kind of antithesis to Western Australia with its original and latent secessionist mentality. In this sense, the political structure of a federation is the most archipelagic of national arrangements. This fact is strangely related to the occasional appearance of Tasmania as mise-en-abyme for the island nation-continent as a whole, a micro-nation, like Darwin’s islands, a micro-duplication of the whole story, or as an archipelagic entity of the global South that expands to include literary sub-regions like the Bass Strait Islands or an off-shore Antarctica (see Mead, ‘Nation, Literature, Location’ 558; Scott; Polack; Leane; Nikki Gemmell, Shiver 1997). A large part of the distinctiveness and value of islands is the fact that they evolve in isolation, becoming worlds of their own. The literature of Tasmania draws on and adapts all of these multiple and overlapping insular imaginaries, even while it begins with and returns to the place and history of a specific island region.

A small detail of the history of education in Australia is perhaps suggestive here: school children in the 1950s and 60s often used a small plastic stencil of the continent of Australia for drawing outline maps of the country. It had perforations to mark the borders of states and territories, but didn’t include Tasmania. The instructions that accompanied the stencil advised that ‘Tasmania is to be drawn freehand.’ Tasmania, then, is not part of the whole, which is why it is prone to be left off maps of ‘Australia’ – as it was, notoriously, at the opening ceremony of the 1982 Commonwealth games. At the same time it is less geographically conventional, less continent-bound, less predictable, a freer space in relation to national territory and political tradition. It has to be conjured by the cartographical imagination, turned upside down, drawn freehand. ‘There’s Tasmania as place, and Tasmania as states (many) of mind’ (Kinsella, Spatial Relations 289).

-

These characteristically Tasmanian literary and textual aspects of the insular imaginary can be viewed alongside or within the frame of the loose disciplinary ensemble of Island Studies, one of the variously spatial paradigms of humanist knowledge that is superseding the temporal paradigm of postcolonialism and its cognates. A major impetus behind the opening up of island studies was Robert MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson’s discipline-founding work The Theory of Island Biogeography (1967) a reminder of how islands ‘have been especially instructive because their limited area and their inherent isolation combine to make patterns of evolution stand out starkly’ (Quammen 19). Behind that study was the crucial role of islands in Darwin’s thinking about evolutionary theory and his contemporary Alfred Russel Wallace’s study Island Life (1880). Along one line of ecological thinking, biogeography has helped to develop a cultural inflection of this discipline that connects the ecological science of insularity, for example, with the discourses of the bioregional imagination (see Robin, 'No Island is an Island' and 'Seasons and Nomads'). The distributed network of Island Studies (including nesology and nesosophy – the wisdom of islands) is a global archipelago of discourses about islands and insularity (see also Quammen 86-88; Shell 21). Islands are now used to think about cultural environment and history as much as about evolutionary developments. The institutions of Island Studies include the Institute of Island Studies at Canada’s University of Prince Edward Island which publishes the Island Studies Journal (ISJ); the Journal of Island Studies (Japanese Society of Island Studies, Hitotsubashi University, Tokyo); Shima: the International Journal of Research into Island Cultures; the Scottish Centre for Island Studies; the journal of the RETI: The Network of Island Universities; the International Small Island Studies Association (ISISA) at the University of Hawaii; the Islands and Small States Institute at the University of Malta; and numerous other forums and NGOs with an island development or resources focus (see Laurie Brinklow, ‘The Proliferation of Island Studies,’ The Griffith Review 34 [2011], pp. 1-6). A forerunner of this network of institutions was the American Institute of Islandology (1945) ‘whose first purpose,’ as Marc Shell points out in his Islandology: Geography, Rhetoric, Politics (2014) was determining whether Australia was an island or a continent’ (7).

Shell’s Islandology offers an historically overarching and compendious discourse, as well as set of reading strategies, for this distributed-area studies. This islandology, both a rhetoric and science of islands, reveals numerous important historical and political aspects of human thinking about islands that are relevant to the history of Tasmanian culture. For example: ‘the modern tendency to confuse circumferential natural borders with political ones and the ancient inclination to except circumferential seas from imperial sovereignty’ (6). Shell’s assertion here suggests the question: is the uncertain place of Tasmania in the cartography and territorial imaginary of modern Australia a sign of its ambivalent role in a sovereign state? A place for ‘island’ or non-mainland, that is non-mainstate, purposes and functions like incarceration and detention, territorial exclusion, epidemiological research, political exile, quarantine, defence (border protection), wilderness tourism, exceptional economic zones, forgetting?

A similarly political edge to the geopoetics of insularity emerges in the thinking of postcolonial critics like Antonis Balasopoulos (‘Nesologies’), John Gillis (Islands of the Mind), Grant McCall (‘Clearing Confusion in a Disembedded World’) and Suvendrini Perera. Of specific interest in this connection is Perera’s monograph study, Australia and the Insular Imagination (2009) which reads such cultural forms and expressions as the national anthem (‘girt by sea’), Max Dupain’s iconic photographs of the beach, and Neil Murray and Christine Anu’s popular song ‘My Island Home’ as figures – sometimes symptomatic, sometimes critical – of an ambivalent national geopolitics of racism, excision and exclusion, most obvious in the history and contemporary reality of border control. The unruly metaphorics of island and continent lies at the heart of this reading. Perera’s study privileges the age of the continent, or the nation, a ‘singularity understood as whole and self contained, a monadic landmass at once severed from its surroundings and protected against them by encircling oceans’ (18). Therefore it begins with and keeps returning to Edmund Barton’s rallying cry for federation in Sydney in 1897: ‘for the first time in history, we have a nation for a continent, and a continent for a nation.’ Barton wasn’t thinking of a pluralised continent or off-shore fragments of the nation to come. In the late nineteenth century scientists were yet to distinguish between ‘continental’ and ‘oceanic’ islands. Perera’s reading, then, runs counter to McCall’s proposition, arising out of his study of Pacific island states, of ‘nissology,’ the ‘studying and understanding of islands on their own terms,’ not continental ones (82). It is not surprising that Perera’s continent-think barely mentions Tasmania, with its earlier provenance in the age of islands and its complex border history – her continental version of the insular imagination leaves Tasmania off the map (see Gillis 124).

Contemporary philosophy has drawn on the rhetoric of insularity in its thinking about the foundation of human being. Jacques Derrida’s final lectures and seminars at the École des hautes etudes en sciences sociales in Paris, from 2001 to 2003, gathered and translated under the title of The Beast & the Sovereign have at their centre a long meditation on Robinson Crusoe. This meditation is twinned with Heidegger, with threads back to Montaigne, but it is Defoe’s fiction that enables Derrida to think about the sovereignty and being of the self. The idea of the island, as philosophers such as Derrida recognise, is an objective correlative for thinking about ourselves and the world, and the literature of islands, including metaphysics, embodies the contradictions and complexities of this thought. Are we enisled in our individual selves, whether singular or plural, or able to connect with other islands or selves, in collectives or communities? Do we even know what being or the world are, except to ask questions about them? (97). It is thinking about Crusoe’s situation that prompts Derrida’s insight: ‘The world is an island whose map we do not have’ (101). Hillis Miller’s reading of Derrida points to the tragic rigour of Derrida’s conclusion, and the antithesis to the thinking of Husserl, Lévinas and Nancy, immanent within the literature of insularity: ‘speaking apparently for himself as much as for Crusoe’s experience of solitude, Derrida firmly asserts that each man or woman is marooned on his or her own island, enclosed in a singular world, with no isthmus, bridge, or other means of communication to the sealed worlds of others or from their worlds to mine’ (265). As here, the literature of islands, which includes the literature of Tasmania, provides distinctive and sometimes radically other perspectives on the individual, the family, the community, the nation, the world. A.D. Hope, for example, a poet who spent his childhood in Tasmania, agrees precisely with Derrida in his poem 'The Wandering Islands':

You cannot build bridges between the wandering islands;

The mind has no neighbours, and the unteachable heart

Announces its armistice time after time, but spends

Its love to draw them closer and closer apart.

-

There are three Tasmanian writers I’d like to draw attention to in this introductory context: the mid-19th-century Van Diemen’s Land sojourner Tom Arnold, the early 20th-century literary historian and scholar Frederick Sefton Delmer, and the folklorist, popular historian and life-writer Patsy Adam Smith. Their times, their personal histories and their trajectories as writers are all very different but together they are emblematic of the individual and territorial heterogeneity of the literature of Tasmania, of the unpredictable relations between a writing life, a literary region and the world. They are each writers whose experience is at a tangent, in different ways, to Tasmania, sometimes self-consciously so, while, at the same time, they suggest the depth and richness of Tasmanian literary culture.

-

Tom Arnold (1823-1900) was one of the Rugby educationalist, Dr Thomas Arnold’s sons, the younger brother of Matthew. After school at Winchester and Rugby, then Oxford, Arnold tried the Law and a clerkship in the Colonial Office. Troubled by a social and religious conscience, though, as he would be for the rest of his life, Arnold emigrated to New Zealand in 1848, intending to farm land his father had purchased near Wellington. Arnold had enjoyed a close personal friendship with Arthur Hugh Clough, at school and later at Oxford and the letters between Arnold and his friend while he was in New Zealand are revealing documents in the colonial romance with the antipodes, as well as being part of the developing context of Clough’s poetics of Victorian pastoral and his loss of faith. They also hark back to the aesthetics of Arnold and Clough’s ‘long-vacation pastoral’ and reading parties of their Oxford days, and forward to the fictionalised portrait of Arnold, Philip Hewson, in ‘The Bothie of Tober-na-vuolich,’ which Arnold read in Tasmania:

I shall see you of course, my Philip, before your departure;

Joy be with you, my boy, with you and your beautiful Elspie.

Happy is he that found, and finding was not heedless;

Happy is he that found, and happy the friend that was with him.

So won Philip his bride: –

They are married and gone to New Zealand.

Five hundred pounds in pocket, with books, and two or three pictures,

Tool-box, plough, and the rest, they rounded the sphere to New Zealand.

There he hewed, and dug; subdued the earth and his spirit;

There he built him a home; there Elspie bare him his children,

David and Bella; perhaps ere this too an Elspie or Adam;

There hath he farmstead and land, and fields of corn and flax fields;

And the Antipodes too have a Bothie of Tober-na-vuolich. (86-87)

In 1849 Lt-Governor William Denison of Van Diemen’s Land offered Arnold the senior position of head of public education. Arnold is an important figure in the development and administration of education in Tasmania. He arrived at the beginning of 1850 and began the job of Inspector of Schools, travelling throughout the island, mostly on horseback, inspecting schools, reporting on teaching conditions and helping to establish a Normal School for the training of teachers. Arnold describes his time in Tasmania in chapters IV and V of his memoir, Passages in a Wandering Life (London: Edward Arnold, 1900), an unfairly neglected work of Tasmanian life writing. He describes teaching Aboriginal children at the Orphan School in New Town. Soon after he arrived in Hobart Arnold met Julia Sorrell, the grand-daughter of Anthony Fenn Kemp (on her mother’s side) and grand-daughter of a former Lt-Governor, William Sorrell (on her father’s side). They were married in June 1850; their first child, Mary Augusta, was born in New Town and would become the novelist Mrs Humphrey Ward. In Passages in a Wandering Life, Arnold describes a life-changing moment in a Tasmanian ‘country inn’ where he had to pass the night on one of his school inspection trips:

I found a number of books; among these was a copy of Butler’s “Lives of the Saints,” in many volumes. Never having heard of the book before, I took out a volume at random, and opening it, happened to fall upon the Life of St. Brigit of Sweden. This saint, who was aunt or cousin to the reigning king of Sweden, was married, and had eight children; nevertheless she lived a most holy and self-denying life, adhering to and obeying the Catholic Church as strictly as St. Ignatius or St. Irenaeus […] The impression which this life made upon me was indelible. […] The final result was that I was received into the Roman communion (by Bishop Willson) at Hobart Town in January 1856. (154-55)

Willson (1794-1866) was the first Catholic bishop of Tasmania, and a friend of Augustus Pugin and William Ullathorne. After leaving Tasmania in the year of his first conversion Arnold continued his restless career in education, a teacher at John Henry Newman’s Oratory School in Birmingham, favoured candidate for the Chair of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford in 1876 (the same year he published a translation of Beowulf), but ineligible by virtue of another conversion to Catholicism, and finally Chair of English Language and Literature at University College, Dublin, where he was a colleague of Gerard Manley Hopkins and a tutor to James Joyce. Bernard Bergonzi’s biography of Arnold, A Victorian Wanderer: the Life of Thomas Arnold the Younger (Oxford UP, 2003) reveals that Arnold began writing a novel of his colonial experience in Van Diemen’s Land in 1853: ‘it had no title beyond ‘Fragments of a Novel’ and the remnants of it in Arnold’s papers at Balliol are very fragmentary indeed and partly illegible. It has a colonial setting, and a protagonist who mourns the failure of the European revolutions of 1848. “After the Fall of Venice, I made the best of my way back to England, much sobered in mind, not to say soured” […] The ‘idealized picture of the heroine, Lucy Winthrop, is evidently drawn from Julia [Sorrel]’ (7). He doesn’t record having met any of the Irish exiles with whom he overlapped in Van Diemen’s Land but if he had, Arnold would surely have sympathised with their political ideals.

-

Frederick Sefton Delmer’s death, at his villa in Rapallo, on a sunny afternoon in 1931 was reported in the Hobart Mercury for 15 July and his tombstone in Rapallo bears the inscription about his Tasmanian origins (Fletcher 154). Delmer was born in Hobart in 1864, the son of a Battery Point Irish whaler (and later Deputy Harbourmaster) and a Hobart dress-maker. He went to school in Battery Point and at Officer College in the Glebe and became a teacher in small towns in northern Tasmania, before leaving the island in 1889 to study towards a BA at Melbourne University. He achieved first class honours in French and German and many prizes, but curiously didn’t graduate. In fact he never gained a university degree (Fletcher 6). In Melbourne he began his lifelong friendship with Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton. He was briefly a teacher at Sydney Grammar, where he introduced the poetry of Christopher Brennan and Dowell O’Reilly (the father of Eleanor Dark). In 1894 he won a travelling scholarship to Europe where he embarked on a self-guided tour of universities, eventually settling in Berlin where Christopher Brennan had recently studied and where he was taught by the philologist Herman Grimm. Grimm became an admirer and patron of Delmer and assisted his first appointment to the University of Königsberg (Kant’s university). Then in 1901 he was appointed to a Lectureship in English at the University of Berlin. In 1905 he published a translation of Gustav Frenssen’s bestselling novel Jörn Uhl and in 1910 his English Literature from “Beowulf” to Bernard Shaw: for the use of Schools, Seminaries and Private Students appeared (Berlin: Weidmann 1910, 1911, 1912; London: Heath Cranton and Ouseley 1913). This history of English literature has been continually in print up until the present and is currently published by Weidmann (Berlin) in their ‘Elibron Classics’ series. Delmer’s history of English literature, then, has been the standard history and reference book for all German upper-secondary and university students for more than a century. During World War I Delmer was interred in the Ruhleben camp for British civilians on the outskirts of Berlin, where he was the first chair of the camp’s literary and debating society. After his release in 1917, he travelled to England where began another career as a journalist with the Daily Mail. He spent the last decade of his life working as a journalist, translator and interpreter in Germany and in Italy, where he became a friend of Ezra Pound. A notebook that Delmer kept in Rapallo records his conversations with Pound, about whose poetry he published a critical article. (See Denis Sefton Delmer, Trail Sinister, 1961, John Fletcher, Frederick Sefton Delmer: from Herman Grimm and Arthur Streeton to Ezra Pound, 1991 and Delmer Family papers in the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, MLMSS 5998/1.)

-

For Patsy Adam-Smith (1924-2001), born in country Victoria and brought up by itinerant railway workers, Tasmania was a place of both unhappiness and enabling experience. In the late, second volume of her autobiography, Goodbye Girlie (1994) Smith writes of her entrapped life as a divorced, single mother in Ulverstone, looking north across Bass Strait. She had gone to live in Tasmania in the late 1940s where her war-time marriage to ‘the father of my children’ had ended in divorce and small-town scandal. But Tasmania is also where she begins her life as a writer. In the early 1950s, and after an already adventurous episode as a service-woman in World War II, ‘I wrote my first book [Re-Discovering Northwest Tasmania, Pat Beckett and Piet Maree] in partnership with the husband of my friend Hans Maree at their home ‘Lonah.’ Hans was a folk artist who became my closest friend, until we both escaped from Tasmania some years later. Her husband, Piet, owned a publishing house in Holland’ (Goodbye Girlie 107-8). The Dutch community is important here, as the book focuses on the Netherlanders who settled, post-war, along Tasmania’s north-west coast in Penguin and Ulverstone.

Patsy’s first escape was to that interstitial zone, Bass Strait and its islands, first on the Sheerwater and then on the Flinders and Cape Barren Island trader Naracoopa, mixing with muttonbirders, craymen, and coastal traders. (Like Eleanor Alliston, Patsy Adam Smith escapes to Bass Strait and its islands, from another island, and also like Alliston, Smith’s writing is associated with and enabled by escape.) In Bass Strait her interest in Australian folklore, community, popular and oral history, and the eccentric outliers of Australian society, like the piners of the Gordon and the Prince of Rasselas (Ernie Bond) is forged. A defining aspect of this early Bass Strait experience is also her discovery of the unofficial history of Tasmania that was settled – however violently and exploitatively – before the official incursions of Bowen, Collins and Paterson. There was a Ship (1967) tells the story of her first adventures as a lone woman maritime officer in the Bass Strait while The Moonbird People (1965) tells the story of the Strait’s unofficial, multi-racial pre-history. This settlement of the Bass Strait islands began with the wreck of the Sydney Cove in 1797 and the discovery of seal colonies during the rescue of survivors on Preservation Island, one of the Furneaux group. Smith claims that by the turn of the century, before ‘mainland’ settlements, the islands already supported a population of around 200, mainly sealers, many of them originally North American. In Tiger Country (1968) Smith again stresses her sense of being a writer of ordinary experience and extraordinary places, rather than of official and public history: during the Sydney Sparkes Orr, Hursey Waterside Workers, and ‘Spot’ Turnbull lottery bribery scandals and associated legal cases of the 1950s, she is in remote parts of Tasmania, like the south-west, living with and writing about bushmen and the Tasmanian environment: ‘No one asked me to cover the things Tasmania is famous for – convicts, Port Arthur, and apples’ (Tiger Country 1-2). Smith’s other volumes about Tasmania, several in collaboration with pre-eminent artists and photographers, include Historic Tasmania Sketchbook (1977), Port Arthur Sketchbook (1977), Tasmanian Sketchbook (1977) and Islands of Bass Strait (1978).

-

These three writing lives are engagements with Tasmania, or that emerge from Tasmania, but not by Tasmanian authors in any obvious or usually recognised sense. Yet the lives and works of writers like these belong to the multi-faceted literary heritage of important contemporary writers like Richard Flanagan, Amanda Lohrey, Carmel Bird, Stephen Edgar, and Peter Conrad, all with significant national and international reputations and in the cases of Flanagan, Edgar and Lohrey, the winners of major literary prizes. Flanagan’s fiction is focused on the tragic encounter of European lives with the antipodal landscapes and society of Tasmania (wilderness guides and Hydro workers), Edgar’s poetry has developed a brilliant intensity of spatial imagination, while Lohrey’s fiction explores the failure of the ideals of the liberation movements of the 60s in the lives of intellectuals and politicians, and the search for spiritual enlightenment in a postmodern world. Carmel Bird’s protean career as a writer has spanned literary fiction, crime and comic novels, children’s writing, short fiction anthologies, memoir (Fair Game: A Tasmanian Memoir, 2015) and a number of guides to creative and life writing. Peter Conrad, like the 19th-century novelist, ‘Tasma,’ is a voluntary exile, writing out of a sophisticated northern hemisphere context, in the genres of memoir and cultural history. Like ‘Tasma’ also, Conrad’s Tasmanian childhood unforgettably shaped his writing self. Willing to speculate on this bioregional imaginary, Conrad pushes the concept of insularity deep into the individual psyche: ‘Insularity is a Tasmanian Creed. On the island, every man is – or wants to be – an island’ (112). This insight, however speculative it might seem, reverberates through all these writers’ works and lives.

-

Read on to the next section: Continuing Aboriginal Writing and Indigenous History.

You might be interested in...