AustLit

-

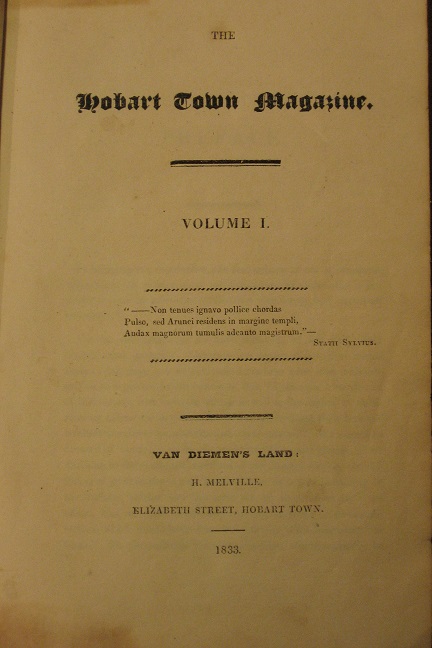

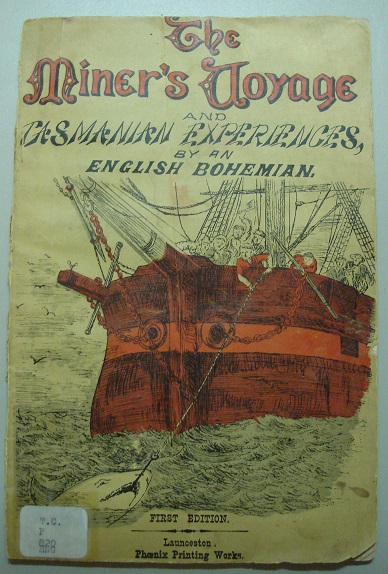

One of the most important aspects of the literature of Tasmania is its unique history of literary production, including the part it has played in the history of the book and print in Australia. The important relation between the press of the early colony and its cultural and political development is well recognised in early Tasmanian print histories. These newspapers also showcased and helped to support local writers. In his 1916 history of ‘The Early Tasmanian Press, and its Struggle for Freedom,’ for example, Herbert Heaton notes ‘at least forty newspapers’ in the first fifty years of the colony: ‘weeklies, fortnightlies, monthlies, and quarterlies […] sporting papers, teetotal advocates, church newses, and Irish exiles’ leaflets’ (1). The Derwent Star and Van Diemen’s Land Intelligencer was the first newspaper, printed in 1810, on the small hand-press that David Collins had brought with him to the colony in 1804. See the section ‘Tasmania’ in D.H. Borchardt, ‘Printing Comes to Australia’ in D.H. Borchardt and W. Kirsop, eds The Book in Australia : Essays Towards a Cultural and Social History (Monash University: Historical Bibliography Monograph No. 16, 1988). The Mercury was founded in 1854 by John Davies, the Launceston Examiner in 1842 and the Burnie Advocate in 1899, all evolving out of and subsuming numerous predecessor papers. (See also J. Moore-Robinson, Chronological List of Tasmanian Newspapers from 1810 to 1933 [1933].) In his ‘Literary Beginnings in Tasmania: a brief survey’ and Pressmen and Governors E. Morris Miller includes histories of the early publishers, editors and printers Andrew Bent, Henry James Emmett, Evan Henry Thomas, William Gore Elliston, Henry Melville, Robert Lathrop Murray, Thomas Richards, James Knox, James Ross, and Nathaniel Lipscombe Kentish. This local periodical culture was intertwined, in colonial readership, with the stream of periodical publications of many kinds from Britain (see Ferrar diaries and Adkins, Reading in Colonial Tasmania). There is some archival evidence of the history of convict reading. There were libraries for convicts at Port Arthur and Point Puer and in the late probation stage, roughly the decade between the late 1830s and late 1840s, probation stations included libraries for convict reading, probably mostly christianizing, instructional and self-improving texts, but some fiction as well (see Adkins, ‘Convict Probation Station Libraries’).

As it happens, the naturalist writer Charles Barrett (see 'Place') was also a book historian and in his edited volume, Across the Years: The Lure of Early Australian Books(1948), he includes chapters on ‘The Early Tasmanian Press and Its Writers’ by Morris Miller and ‘Van Diemen’s Land for the Collector’ by Clive Turnbull. One of the useful inclusions of Turnbull’s chapter is about the Van Diemen’s Land or Hobart Town Almanacs. Turnbull rightly notes that these ‘contain an extraordinary variety of information, some entirely irrelevant to their prime purpose but now of great antiquarian interest. Some, likewise, have a definite typographical charm and their illustrations are by no means to be disdained’ (57).

Other important publications of this kind are Walch’s Almanac (1863-1970) and Walch’s Literary Intelligencer and General Advertiser (1859-1916). The Intelligencer included information about book arrivals from overseas, literary notices and reviews (some syndicated), as well as artistic, scientific articles, some original creative work and advertisements. Its motto, from Juvenal, was ‘Scire volunt omnes, mercedem solvere nemo’: ‘Everyone wants to know but no-one wants to pay the price.’ J. Walch and Sons was a very successful printing, book importing, musical instrument, stationery and publishing family company in Hobart, with a London office from the late nineteenth century until 1961, and was finally dissolved only in 2003.

The Tasmanian Review was started by Andrew Sant and Michael Denholm in 1979, later morphing into Island magazine in 1981, one of the important little magazines on the contemporary literary scene. GLBT and marriage equality activist Rodney Croome was editor of Island magazine from 1995-1999. Croome has been widely recognized for his work in the 1990s in helping to change what had been Tasmania’s discriminatory laws against sexual and gender minorities, laws with links to the colonial and carceral origins of the state and to social attitudes that persist into the present. Croome has published two important records of his work in these areas of social activism: WHY vs WHY: Gay Marriage (Pantera, 2010) and From This Day Forward – Marriage Equality in Australia (Walleah, 2015). 40º South (from 1995) is an upmarket tourist and lifestyle magazine that also regularly publishes literary work. The bi-annual Famous Reporter and Walleah Press have published a varied range of contemporary poetry, short fiction, interviews and essays. The subset also contains some brief histories of Tasmanian publishers, including J.B. Walch & Sons, and the Blubber Head, Cat & Fiddle (Fullers’), Oldham Beddome & Meredith (OBM), Walleah, Wattle Grove, Glendessary and Cornford presses.

-

Some of the most important figures in Australian book collecting, like William Walker, Robert Sticht, W.E.L. Crowther, E. Morris Miller and Charles Barrett have also been Tasmanians, or resident there during their lives as collectors. Book collecting, bibliomania, biblio-philanthropy, the obsessive mentality of collecting and book fetishism are all interesting and enigmatic conditions – ‘a gentle madness’ in Nicholas Basbanes’s study – and Tasmania has some particularly compelling cases to offer.

-

William Walker was born in Hobart in 1861, studied civil engineering at Melbourne University and devoted his fortune from mining and railway shares to book collecting and library philanthropy. As Heather Gaunt has uncovered, Walker seems to have developed his sense of book heroism from his reading of Thomas Carlyle in essays like ‘The Hero as Man of Letters’ (Gaunt 10). This cultural idealism was shared and re-enforced by Walker’s professional friendship with Morris Miller, who represented a very effective conjunction of idealism (his first book was on Kant) and pragmatism (he also wrote the first Australian monograph on librarianship, Libraries and Education, 1912). This intellectual impetus of Walker’s was fused with a charged moment of discovery that he recounts, as a young man, of a three-volume Quintus Servinton in ‘a second-hand shop in Melbourne around 1880’ (Gaunt 109). This very rare copy of Savery’s novel is now in the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office. Notably, Walker was also a collector of Australian popular fiction and of erotica. The rich holdings of Louis Becke, Nat Gould, Guy Boothby and Ethel Turner, amongst others, in the Tasmaniana library of the State Library of Tasmania are a legacy of this interest (Gaunt 12). Walker’s obsession with Tasmanian colonial texts, like The Hermit in Van Diemen's Land: from the Colonial Times, his collecting of early Australian and Tasmanian publications, together with his later interests in popular fiction, indicates that his interests were never narrowly literary. He had an interest in the broader culture of literary production and of book history, both locally and nationally. Ten years younger than Sir John Quick (1852-1932), and twenty years older than Sir John Ferguson (1881-1969) and Morris Miller (1881-1964), Walker shared these bibliographers’ and librarians’ devotion to Australian book history but not their vision of a canonically centred and scholarly based infrastructure. Walker made foundational donations to the Tasmanian Public Library during his lifetime and his will provided for his remaining books to go to the library after his death. Walker’s import of large numbers of pornographic books involved a special import postal licence and how he managed this activity remains an untold chapter in the history of banned books in Australia. What exactly happened to this large collection after his death also remains a mystery (see Mead, ‘What happened to the Walker books?’).

-

Robert Carl Sticht (1856-1922) was a very different kind of bibliophile but just as interesting. So interesting in fact that Sticht and his legend are represented in Geoffrey Blainey’s history The Peaks of Lyell, in Marie Bjelke Petersen’s novel of the West coast of Tasmania, Dusk (where he appears as the character Jack Terrigan), and in Jan Senberg’s paintings of the Queenstown minescape (see Haynes 260). Where Carlyle was Walker’s inspiration, Sticht’s seems to have been Goethe. Born in Hoboken, New Jersey, Sticht was a US and German trained metallurgist and mining engineer who came to Tasmania in 1895 to manage the new Mount Lyell Company mine at Queenstown. He made a fortune for the mine out of a pyritic smelting technique that he invented and in 1903 was both the most highly paid man in Tasmania and possibly the most remotely located. Queenstown was only accessible by sea at this time, near Macquarie Harbour, the site of the old penal settlement. His later years were troubled financially but he lived on at Penghana, the mine manager’s house on top of the highest hill in Queenstown that he had built in 1898. It included a heritage garden, currently under restoration. Sticht died in 1922 having spent his last years in cataloguing his collection in five 180-page volumes arranged by Penghana’s rooms – den, front hall, back library etc. (Gaunt, ‘Library’ 15). Sticht turned Penghana into a remote, jealously guarded cave filled with thousands of books, collected mostly between 1900 and 1913. Unlike Walker, with his interest in nineteenth-century Australian and popular publications, Sticht was interested in manuscript, print and typographic treasures of global value and significance. After his death in 1923 Sticht’s library was auctioned in Melbourne and the Melbourne Public Library and Art Gallery bought up a large proportion of his collection. The collection of early typographical works, bought by the Felton Bequest for the Melbourne Public library consisted of 2,200 items (Gaunt, ‘Library’ 1). Sticht also collected Australiana and Tasmanian historical documents and books from James Backhouse Walker and J.W. Beattie. The provenance of some of Melbourne’s most valuable library holdings, then, lies in the mineral wealth of the remote West coast of Tasmania. Heather Gaunt’s published research into Walker, Sticht and the wider role of libraries in the formation of national culture and public memory has important perspectives on Tasmania’s role in this cultural history.

-

W.E.L.H. Crowther and E. Morris Miller are also significant figures in this field of Tasmanian print history. Crowther was the great-grandson of William Crowther, the early Hobart medical practitioner, and specialised in collecting Tasmaniana. Inspired by David Scott Mitchell in Sydney and William Walker in Hobart, he donated his collection to the State Library of Tasmania in 1964. E. Morris Miller, appointed to the University of Tasmania in 1913 and later Vice-Chancellor, was a founder of library studies in Australia and the first great bibliographer of Australian literature. Michael Roe devotes a chapter to Morris Miller in his 1984 study Nine Australian Progressives : Vitalism in Bourgeois Social Thought 1890-1960.

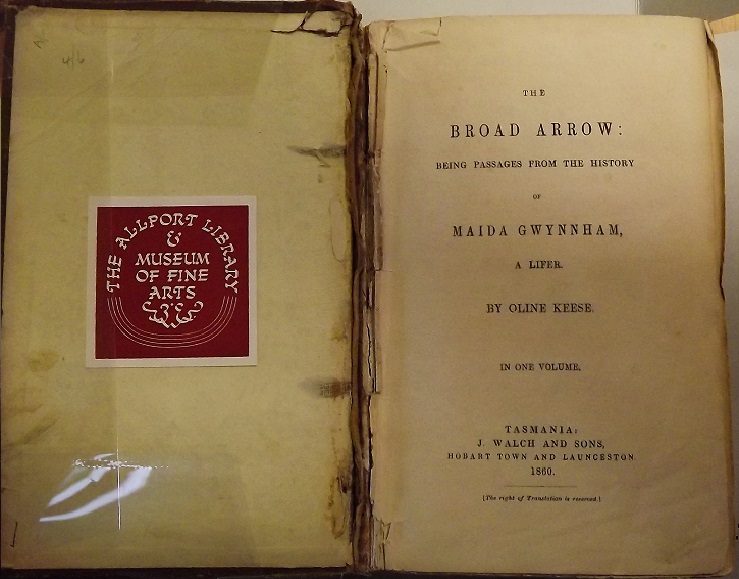

Clifford Craig’s (1896-1986) Notes on Tasmaniana: A Companion Volume to the Engravers of Van Diemen’s Land, Old Tasmanian Prints and More Old Tasmanian Prints (Launceston: Foot & Playsted, 1986) is a first person and very personal account of Craig’s collecting of Tasmaniana over the period 1938 to the 1970s and contains much interesting detail about the history of maps of Tasmania, early printing and publishing, almanacs, Tasmanian bank robberies, ‘Anti-Transportation literature,’ the history of Christ College, Bishopsbourne, early railways and theatres, turning up early lithographs of Van Diemen’s Land in Charing Cross Road antiquarian shops, as well as personal histories of reading William Hay’s The Escape of the Notorious Sir William Heans(1919) and Caroline Leakey’s The Broad Arrow. Craig also made a special study of the Van Diemen’s Land Pickwick Papers, a pirated edition of Dickens’s novel published by the Launceston printer Henry Dowling in 1838 (also the publisher of John West’s History of Tasmania): The Van Diemen's Land Edition of the Pickwick Papers : A General and Bibliographical Study with some Notes on Henry Dowling(Cat & Fiddle, 1973). Perhaps like elsewhere, the philanthropy of professional men is aligned with the fetishism of collecting, to the benefit of Tasmania’s archive and its record of Tasmanian-ness.

-

In any history of significant Tasmanian books a short-list of pre-eminent volumes would include the extremely rare Quintus Servinton, other firsts like Pindar Juvenal’s The Van Diemen's Land Warriors, or, the Heroes of Cornwall : A Satire, in Three Cantos, Mary Grimstone Leman’s Woman's Love, The Hermit in Van Diemen's Land, West’s and Robson’s histories, Robertson and Craig’s Early Houses of Northern Tasmania, Mortmain, and the Tasmanian Cyclopaedia. These volumes all have their bibliographical and literary interest but in terms of broad cultural significance, perhaps the single most important book in Tasmanian history is N.J.B Plomley’s edited volume,Friendly Mission: The Tasmanian Journals and Papers of George Augustus Robinson, 1829-1834(Hobart: Tasmanian Historical Research Association, 1966; Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, 2008). Greg Lehman has called Friendly Mission a flawed encyclopedia of Aboriginal Tasmania, ‘biblical in its volume and scale […] replete with accounts of creation, slavery and exodus,’ equivalent to Cook’s journals in terms of ‘the development of national narratives.’ As Lehman observes about Robinson’s obsessive writing of his own missionary and conciliatory travels around the island in the 1820s and 30s, ‘buried within Robinson’s ostentatious prose and amateur naturalism is a patchwork of observation and interpretation that constitutes most of what is known of the cosmology and lifestyle of an ancient society in the midst of devastating change’ (‘Pleading’). It is also the accompaniment to a government sponsored ‘final solution’ and includes what must be, for Lehman, the painful forensics of Appendix 4, ‘The Causes of the Extinction of the Tasmanians’ (964-67) (see also Anna Johnston and Mitchell Rolls, Reading Robinson: Companion Essays to 'Friendly Mission'). Because of the vice-like grip of historiographical discourse that has closed around Robinson’s journals, it is rarely recognised that The Savage Crows – to give it Robinson’s proposed title, and the title of Robert Drewe’s own 1976 novel (originally The Genocide Thesis) is another of the great phantom, failed books or isolaria of Tasmanian literature – along with Michael Howe’s Journal of Dreams, Jorgen Jorgenson’s The Aborigines of Van Diemen’s Land, Tom Arnold’s novel of colonial life, and Frank Hurley and Ken Sherrott’s This Other England.

Robinson took his papers and journals with him to England, when he retired to Bath in 1858 and where he worked ineffectively on shaping his narrative out of the vast raw materials of his Tasmanian experience. He was in correspondence with writers of missionary, scientific and archaeological works, like Joseph Barnard Davis (author of Crania Britannica, 1865) and William Barrett Marshall (Personal Narrative of Two Visits to New Zealand, in His Majesty’s Ship Alligator, AD 1834, 1836), about the volume he was writing of his time amongst the Tasmanian Aboriginals. Davis wrote to Robinson on March 2, 1862 that ‘You send me good news when you say, you are about preparing a work on the Aborigines of Van Diemen’s Land for publication’ and in fact offered Robinson’s widow, after his death in 1866, assistance with writing the book (Robinson papers, Mitchell Library, A7089-1, p. 475; 569). As Robinson’s correspondence with the painter John Glover indicates, this book had been planned and discussed for more than a decade. On July 16, 1835 Glover had written to Robinson in Hobart about how he had ‘great pleasure in beginning a plate for your book […] I write also to know how long a time you can conveniently allow me before you publish’ (Robinson papers, Mitchell Library, A7058, p. 398). This picture was probably ‘View near Brighton, Tasmania, with camp of Tasmanian Aborigines’ and Glover had addressed his letter to Robinson as ‘Governor of the Blacks.’

-

In other words, all Robinson’s journal and report writing had behind it the intention of a ‘narrative’ and it’s hard not to imagine that this narrative didn’t have, in his mind, some kind of literary shape, however inchoate and cloudy. Given his lack of formal education, the genres of missionary, scientific and exploratory writing that his correspondents exemplified must have seemed daunting if not impossible. Equally daunting, but perhaps more tantalising, were the more literary forms of imperial ethnography and missionary narrative, suggested perhaps by a handwritten ms amongst his papers, ‘A Short Dialogue between a Master & Servant’ (1858). But Robinson’s literary pretensions are also suggested by scattered moments of lyric insight and metaphysical speculation in the Friendly Mission journals, as Greg Lehman notes, and most strikingly in the vision of children and burning trees at Wybalenna in his journal for 25 September, 1837 (Weep in Silence, pp. 479-80). We know that Robinson must have read and admired Thomas Moore’s enormously popular 1817 ‘oriental romance’ Lalla Rookh: the name he gave to Truganini in a renaming ceremony on Flinders Island on 15 January, 1836 (Weep in Silence, pp. 336-37). (Ships, houses and gold mines were also named ‘Lalla Rookh’.) Perhaps he also absorbed Moore’s schemata of a non-Christian, chaotic uncivilization awaiting ‘the rationalizing influence of European Empire’ and Christianity (Brown 23). And at the beginning of his journal writing in 1829, where he notes in only his third entry (for 1 April) – ‘6am got under way; fair weather, adverse winds. Traversed the shore. Saw remains of the natives’ fires. Reached Little Cove [North Bruny Island]; remained here this night. Saw footmarks of natives on the shore’ (p. 54) – he must have been thinking of himself as George Augustus Robinson Crusoe, another English castaway and narrator of remote island life. In the end, the only thing Robinson published, in Bath, was a pamphlet of five poems, Stray Lyrics (Bath: Meyler & Son, 1858). But his Robinsonade that he returned from his Island of Despair to his other island, England, to write was only completed by his Tasmanian editor N.J.B Plomley – a foundational, if problematic, Robinsonade for a reader like Greg Lehman.

This recognition of the narrative and literary tradition that ghosts Robinson’s journals of his time amongst the Tasmanian Aborigines also helps an understanding of the fictional threads in Australian literature more broadly that those journals have done much to engender: Robert Drewe’s The Savage Crows, Mudrooroo’s Doctor Wooreddy's Prescription for Enduring the Ending of the World (1983), Richard Flanagan’s Gould's Book of Fish (2001), Craig Cormick’s Of One Blood: the Last Histories of Van Diemen’s Land (2007) (see also Robert Drewe, ‘The Savage Crows: A Personal Chronology,’ Kunapipi 5.1 1983: pp. 65-72).

-

Read on to next section: Conclusion.

You might be interested in...