AustLit

Latest Issues

AbstractHistoryArchive Description

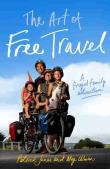

'Patrick, Meg and their family had built a happy, sustainable life in regional Victoria. But in late 2013, they found themselves craving an adventure: a road trip.

'But theirs was a road trip with a difference. With Zephyr (10), Woody (1) and Zero their Jack Russell, they set off on an epic 6,000km year-long cycling journey along Australia’s east coast, from Daylesford to Cape York and back.

'Their aim was to live as cheaply as possible − guerrilla camping, hunting, foraging and bartering their permaculture skills, and living on a diet of free food, bush tucker, and the occasional fresh road kill. They spent time in Aboriginal communities, joined an anti-fracking blockade, documented edible plants, and dodged speeding cars and trucks on the country’s most dangerous highways. The Art of Free Travel is the remarkable story of a rule-breaking year of ethical living.'

Source: Publisher's blurb.

Publication Details of Only Known VersionEarliest 2 Known Versions of

Works about this Work

-

Land, Labour and Food : Art and the Recovery of Ecological Livelihoods

2016

single work

criticism

— Appears in: Axon : Creative Explorations , November vol. 6 no. 2 2016; 'In his book The perception of the environment (2011), anthropologist Tim Ingold critiques a paradigmatic opposition that has long underpinned modern understandings of western civilisation: the opposition of practices of food production (agriculture) to practices of food collection (hunting and gathering). He points out that underlying this opposition ‘is a master narrative about how human beings, through their mental and bodily labour, have progressively raised themselves above the purely natural level of existence to which all other animals are confined, and so doing have built themselves a history of civilisation' (Ingold 2000: 78). While we now recognise the racist logic of modern evolutionist thought, the systematic domination of land and animals remains central to western schema of modernisation. Consequently, we tend not to see the practices of peoples who survived according to a land-based ethic of interdependency and stewardship as equally constitutive of human history. The central injunction of Ingold’s book, one informed by anthropological analyses of many kinds of societies and that applies to both sides of this opposition, is that we properly recognise the ecological character of human ontology. Notwithstanding our cognitive capacity to objectify and set ourselves apart from our world, our subjectivity is formed through our interrelatedness with the human, non-human and material components of our environment. This means that rather than viewing human history as a process by which we have asserted our reason and will upon nature and the other materials of the earth, Ingold urges us to see history as ‘the process wherein both people and their environments are continually bringing each other into being’ (2000: 87).' (Introduction)

-

Land, Labour and Food : Art and the Recovery of Ecological Livelihoods

2016

single work

criticism

— Appears in: Axon : Creative Explorations , November vol. 6 no. 2 2016; 'In his book The perception of the environment (2011), anthropologist Tim Ingold critiques a paradigmatic opposition that has long underpinned modern understandings of western civilisation: the opposition of practices of food production (agriculture) to practices of food collection (hunting and gathering). He points out that underlying this opposition ‘is a master narrative about how human beings, through their mental and bodily labour, have progressively raised themselves above the purely natural level of existence to which all other animals are confined, and so doing have built themselves a history of civilisation' (Ingold 2000: 78). While we now recognise the racist logic of modern evolutionist thought, the systematic domination of land and animals remains central to western schema of modernisation. Consequently, we tend not to see the practices of peoples who survived according to a land-based ethic of interdependency and stewardship as equally constitutive of human history. The central injunction of Ingold’s book, one informed by anthropological analyses of many kinds of societies and that applies to both sides of this opposition, is that we properly recognise the ecological character of human ontology. Notwithstanding our cognitive capacity to objectify and set ourselves apart from our world, our subjectivity is formed through our interrelatedness with the human, non-human and material components of our environment. This means that rather than viewing human history as a process by which we have asserted our reason and will upon nature and the other materials of the earth, Ingold urges us to see history as ‘the process wherein both people and their environments are continually bringing each other into being’ (2000: 87).' (Introduction)

Awards

- Victoria,

- New South Wales,

- Queensland,