AustLit

Latest Issues

AbstractHistoryArchive Description

Reading Australia

This work has Reading Australia teaching resources.

Unit Suitable For

AC: Year 8 (NSW Stage 4)

Themes

culture, family, identity, interracial

General Capabilities

Critical and creative thinking, Ethical understanding, Information and communication technology, Intercultural understanding, Literacy, Personal and social

Notes

-

Ages 2+.

-

This is affiliated with Dr Laurel Cohn's Picture Book Diet because it contains representations of food and/or food practices.

Food depiction - Incidental

Food types - Everyday foods

- Everyday drinks

- Discretionary foods

- High fat foods

- High salt foods

- Fresh foods

- Fast food/Takeaway [fish and chips]

Food practices - Eating in - meal

- Food production

- Food selling

- Food preparation

Gender - Food production - male

- Food selling - male

- Food preparation - female [domestic]

Signage n/a Positive/negative value n/a Food as sense of place - Domestic

- Rural

Setting - Domestic interior

- Rural landscape

Food as social cohesion - Family meals [breakfast, dinner]

Food as cultural identity - White Australian characters

- Non-Anglo characters

- Ethnographic story

Food as character identity n/a Food as language n/a

Publication Details of Only Known VersionEarliest 2 Known Versions of

Works about this Work

-

The Dangers of Reading Globally

2019

single work

criticism

— Appears in: Bookbird , vol. 57 no. 2 2019; (p. 1-11)'This article is based on a keynote delivered at the 36th IBBY International Congress in Athens, Greece, on August 31, 2018. IBBY members are committed to the potentials offered by global literature for opening minds to multiple ways of living in the world and creating intercultural understanding. Asking readers to read outside their comfort zones, however, can instead hold danger and perpetuate stereotypes and misunderstandings. This article proposes that we can address these dangers through acting on our social responsibilities as bookmakers, readers, and educators to balance individual voice with group responsibility and to determine if our actions could cause harm to readers’ understandings of a culture.' (Publication abstract)

-

Acquiring New Languages

2018

single work

column

— Appears in: Books + Publishing , July vol. 98 no. 2 2018; (p. 8-9)'Jackie Tang asks publishers, booksellers and librarians if three is an increased demand in foreign-language children's books.'

-

What Are We Feeding Our Children When We Read Them a Book? Depictions of Mothers and Food in Contemporary Australian Picture Books

2016

single work

criticism

— Appears in: Mothers and Food : Negotiating Foodways from Maternal Perspectives 2016; (p. 232-244)'This chapter explores how Australian writers and illustrators in the twenty-first century depict the act of mothering in picture books for young children in relation to cooking and serving food. It draws on the idea that children’s texts can be understood as sites of cultural production and reproduction, with social conventions and ideologies embedded in their narrative representations. The analysis is based on a survey of 124 books that were shortlisted for, or won, Children’s Book Council of Australia awards between 2001 and 2013. Of the eighty-seven titles that contain food and have human or anthropomorphised characters, twenty-six (30 percent) contain textual or illustrative references to maternal figures involved in food preparation or provision. Examination of this data set reveals that there is a strong correlation between non-Anglo-Australian maternal figures and home-cooked meals, and a clear link between Anglo-Australian mothers and sugar-rich snacks. The relative paucity of depictions of ethnically unmarked mothers offering more nutritious foods is notable given the cultural expectations of mothers as caretakers of their children’s well-being. At the same time, the linking of non-Anglo-Australian mothers with home-cooked meals can be seen as a means of signifying a cultural authenticity, a closeness to the earth that is differentiated from the normalised Australian culture represented in picture books. This suggests an unintended alignment of mothers preparing and serving meals with “otherness,” which creates a distancing effect between meals that may generally be considered nutritious and the normalised self. I contend there are unexamined, and perhaps unexpected, cultural assumptions about ethnicity, motherhood, and food embedded in contemporary Australian picture books. These have the potential to inscribe a system of beliefs about gender, cultural identity, and food that contributes to readers’ understanding of the world and themselves.'

Source: Abstract.

-

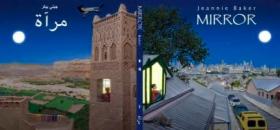

Examining the Interpretations Children Share from Their Reading of an Almost Wordless Picture Book during Independent Reading Time

2015

single work

criticism

— Appears in: The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy , October vol. 38 no. 3 2015; (p. 183-192)'This paper shares findings from part of a larger project exploring students' interpretations of children's literature during independent reading time. Examined in this paper are interpretations by students in Grade 4 (aged 9-10 years) about the messages conveyed in the almost wordless picture book Mirror by author and artist Jeannie Baker. Mirror shares a multicultural perspective on life through its portrayal through collage of the lives of two families living in different countries. Data were collected as semi-structured interviews and observations recorded as field notes. Chambers' (1994) 'Tell Me' framework informed the question schedule of the semi-structured interviews, which were designed to promote opportunities for students to share their interpretations following independent reading time. Emerging themes from data analysis are considered through critical literacy lens (Janks, 2010). Further, implications for the use of almost wordless picture books in classroom reading experiences are identified in connection with the development of children's cultural awareness and sensitivity (Short, 2003).' (Publication abstract)

-

A Similarity or Difference : The Problem of Race in Australian Picture Books

2013

single work

criticism

— Appears in: Bookbird , April vol. 51 no. 2 2013; (p. 13-22) 'The prevailing humanist ideology in fiction produced for children entails that thematic explorations of race usually pivot on the notion that humans are all created equal, regardless of race. However, this position fails to acknowledge the privileged status of whiteness as a racial category. This article examines two recent Australian picture books which explore the relationship between white and non-white identities in an Australian social context, arguing that the construction of whiteness as a normative standard of human experience must be interrogated before genuinely intersubjective race relations can be achieved.' (Author's abstract)

-

[Review] Mirror

2010

single work

review

— Appears in: Bookseller + Publisher Magazine , July vol. 89 no. 9 2010; (p. 43)

— Review of Mirror 2010 single work picture book -

Brilliant Reflections

2010

single work

review

— Appears in: The Canberra Times , 31 July 2010; (p. 24-25)

— Review of Mirror 2010 single work picture book -

Under Age

2010

single work

review

— Appears in: The Sunday Age , 29 August 2010; (p. 21)

— Review of Five Parts Dead 2010 single work novel ; Mirror 2010 single work picture book ; Graffiti Moon 2010 single work novel -

[Review] Mirror

2010

single work

review

— Appears in: Magpies :Talking About Books for Children , July vol. 25 no. 3 2010; (p. 28)

— Review of Mirror 2010 single work picture book -

Parallel Worlds Related through the Looking Glass

2010

single work

review

— Appears in: The Sun-Herald , 19 September 2010; (p. 13)

— Review of Mirror 2010 single work picture book -

Author Engages through Images, Not Words

2010

single work

column

— Appears in: The Sun-Herald , 15 August 2010; (p. 24) -

Fabric of Societies Woven Together To Show Common Ground

2010

single work

column

— Appears in: The Sydney Morning Herald , 20 August 2010; (p. 5) -

Interview: Jeannie Baker

Tracey Slater

(interviewer),

2010

single work

interview

— Appears in: Newswrite : The NSW Writers' Centre Magazine , August/September no. 192 2010; (p. 8-9) -

Judged By More than Their Covers

2011

single work

column

— Appears in: The Advertiser , 16 April 2011; (p. 50-51) -

The Lives of Others Reflected

2011

single work

column

— Appears in: The Courier-Mail , 8 July 2011; (p. 72)

Awards

- 2012 nominated Kate Greenaway Medal

- 2011 shortlisted Australian Book Industry Awards (ABIA) — Australian Book of the Year for Younger Children

- 2011 joint winner CBCA Book of the Year Awards — Picture Book of the Year Joint winner with Nikki Greenberg's Hamlet.

- 2011 shortlisted New South Wales Premier's Literary Awards — Patricia Wrightson Prize for Children's Books

- 2011 winner Indie Awards — Children's

-

cAustralia,c

-

cMorocco,cNorth Africa, Africa,

- Sydney, New South Wales,

-

cMorocco,cNorth Africa, Africa,